Medieval dye baths

HISTORY OF DYEING

“… for by such meanes Saffron was brought first into this realme, which hath sent many poore on worke, and brought great wealth into this realme. Thus may Sumack, the plant wherewith the most excellent blacks be died in Spaine, be brought out of Spaine, and out of the Lands of the same, if it will grow in this more colde climate. For thus was Woad brought into this realme, and came to good perfection, to the great losse of the French our olde enemies. And it doth marvellously import this realme to make naturall in this realme such things as be special in the dying of our clothes.”

- Richard Hakluyt

Before the advent of modern dyes, which are extracted from coal, colours were got from plants and later certain minerals.

Plants that were available to the medieval dyer included cultivated plants such as madder for red, woad for blue, the meadow plants weld and woadwaxen (dyers greenwood) and the imported dyes such as kermes, orchil and brazilwood for richer reds and purples.

Both woad and madder were paying toll at Winchester in the 13th C when woad was being imported from English owned lands in France. Woad was such an important product that woad assayers were set up at Winchester and York.

The Crusades had a direct impact on the dyeing industry as Knights travelled to countries that were dyeing with beautiful and bright colours and bringing samples back. People in England wanted access to the dyes and methods.

1188 saw the first mention of a Dyers Guild in London. This is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London and as such existed as a trade association for members of the dyeing industry.

The Guild systems vigilantly maintained a high standard of quality in the industry. In many countries dyers were graded by the guild system; the master dyers being allowed to use the major “fast” dyes while their lesser colleagues were restricted to the slower ones. In some places it was forbidden to possess, let alone use, major dyestuffs unless you were a member of a guild.

Charters were granted to a large number of towns in England including York and Lancaster. Their role was to protect members against foreign jurisdiction and began to play a larger role in the administration of the towns. Non members were still allowed to trade but had to pay a large fee to authorities for doing so.

In York, weavers were granted the right to make dyed and striped cloth for the whole of Yorkshire.

By the beginning of the 14th Century, the English textile trade began on a large scale and the dyeing industry grew in importance alongside it. Several English towns specialised in colours e.g. Lincoln Green and Beverly Blue. The names Lister, Litster or Litester, meaning dyer, became common surnames.

On May 1st 1326 a law was passed, forbidding the wearing of foreign stuffs, and granting greater liberties to the weavers, fullers, and dyers.

By the early 1500's France, Holland and Germany had begun the cultivation of dye plants as an industry - contributing to the 'unnecessary foreign wares' being imported to England and a reason for the Sumptuary Law of Queen Elizabeth 1.

By the 17th C, there was an international trading network importing dyes from all over the world. Restrictions that had been placed on imports was overturned so that the textile industry and the domestic market’s desire for bright and long lasting colours could be satisfied.

There was also a move towards the cultivation of specialised cash crops in England. The English Improver Improved recommended the growing of herbs and spices for cooking and medicinal purposes as well as industrial dyes – woad, weld, madder, safflower, flax, mulberries for silk worms, hemp and teasels. This was first suggested by the men who travelled in European countries and who saw the commercial advantage of producing these products at home instead of importing them.

“The woolles being naturall, and excellent colours for dying becomming by this meanes here also naturall, in all the arte of Clothing then we want but one onely speciall thing. For in this so temperate a climat our people may labor the yere thorowout, whereas in some regions of the world they cannot worke for extreme heat, as in some other regions they cannot worke for extreme colde a good part of the yere. And the people of this realme by the great and blessed abundance of victuall are cheaply fed, and therefore may afoord their labour cheape.

And where the Clothiers in Flanders by the Flatnesse of their riuers cannot make Walkmilles for their clothes, but are forced to thicken and dresse all their clothes by the foot and by the labour of men, whereby their clothes are raised to an higher price, we of England haue in all Shires store of milles vpon falling riuers. And these riuers being in temperate zones are not dried vp in Summer with drought and heat as the riuers be in Spaine and in hotter regions, nor frozen vp in Winter as all the riuers be in all the North regions of the world: so as our milles may go and worke at all times, and dresse clothes cheaply.

Then we have also for scowring our clothes earths and claies, as Walkers clay, which attains a thickness of 150 feet near Bath. and the clay of Oborne little inferior to Sope in scowring and in thicking. Then also have we some reasonable store of Alum and Copporas here made for dying, and are like to have increase of the same. Then we have many good waters apt for dying, and people to spin and to doe the rest of all the labours we want not.”

- The Principal Naivigations, Voyages and Traffiques by Richard Hakluyt

Bancroft was an 18th century chemist who carried out many experiments with mordanting and dyeing fibres.

One of the best resources on dyeing in Yorkshire are Sam Hill’s pattern books. These show samples of all the dyes he used in his factory at Making Place in Soyland. He was a merchant who exported his cloth across Europe and was one of the wealthiest men in England. You can see the letter Books of Joseph Holroyd and Sam Hill here.

Cotton printing

Dyeing was traditionally carried out on the yarn, rather than the finished piece. In the 18th century printing became one of the major areas of design. Probably one of the most innovative stages in textiles was the discovery of the method for printing indigo using potash, quicklime and orpiment – which became known as English Blue. For the first time, Europeans were able to produce cottons with blue designs on white backgrounds.

Common plant and animal dyes that would have been used

WOAD

Woad is a member of the mustard family and was one of the most common dyes used in England for the blue colour yielded by its leaves. The leaves were dried and then crushed and fermented over a period of several weeks. The smell was so bad that Queen Elizabeth forbade the production of woad within five miles of any her royal estates.

It is perhaps best known as the dye that the ancient Britons used to paint themselves. Caesar is reported to have said "omnes vero se Britanni vitro inficivnt, qvod caervlevm efficit colorem" which translates as "All the Britons dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue colour", although there is some controversy about this.

.gif) Medieval woad dyeing - a very smelly process, evidenced by the people in the background holding their noses

Medieval woad dyeing - a very smelly process, evidenced by the people in the background holding their noses

When dyeing the cloth, it comes out of the dye vat pale yellow and then gradually turns blue through oxidisation.

It was extensively used for dyeing cloth up until the introduction of indigo at the end of the 16th century and since then – it was still being grown in Lincolnshire in the 1920s and 30s to provide dye for Royal Air Force uniforms. It is still produced in France and more recently in Norfolk.

After being bruised, it is formed into balls which are them left to ferment. The colour it gives is not as bright as Indigo but more durable.

When Indigo was first introduced to this country, there was much resistance from the woad growers here and to protect the English economy from imported dyes.

It was Indigo which finally put a finish to the woad trade – in spite of all attempts to stop it, from forbidding its use by law to rumours that it destroyed the cloth itself.

In 2004, the European SPINDIGO (Sustainable Production of Plant-derived Indigo) Project was completed. This project, which included ten partners across Europe, looked at producing woad for the commercial market. It identified the best strains, growing conditions and extraction methods and the environmental impacts of the crop.

MADDER

The roots of the plant are long and slender and were extensively used in the dyeing of red cloth and although not as bright as cochineal, it was cheaper and more durable. Originally a native of Europe and Asia, it has long been naturalised in the UK.

The very best colour that could be obtained - that of a colour closer to carmine than the scarlets of Europe - was due to the very complicated and labour intensive processes used in Turkey. The method defeated the dyers in England for a long time. Cotton fibres received successive steepings in lye, olive oil, alum and dung and the production could take weeks.

In the 13th century its cultivation already yielded considerable revenue in taxes and duties. Norwich appears to have been an important English centre of the trade, as the name of one of its streets, Madder Market, would seem so suggest.

The difficulty of producing a bright red is mentioned in a letter dated April 1738 from Escrike, a Lancashire manufacturer, to Wilson and Harrop of London:

“I think those (fustians) you order for rose colour and scarlet ingraine had much better been sent up in the gray cut … you dye them much better than we can in this country. We pay a guinea an end for dyeing scarlet and a very poor colour. They will not dye for washing red a good full colour for 7s 6d per end, but shall leave it to you.”

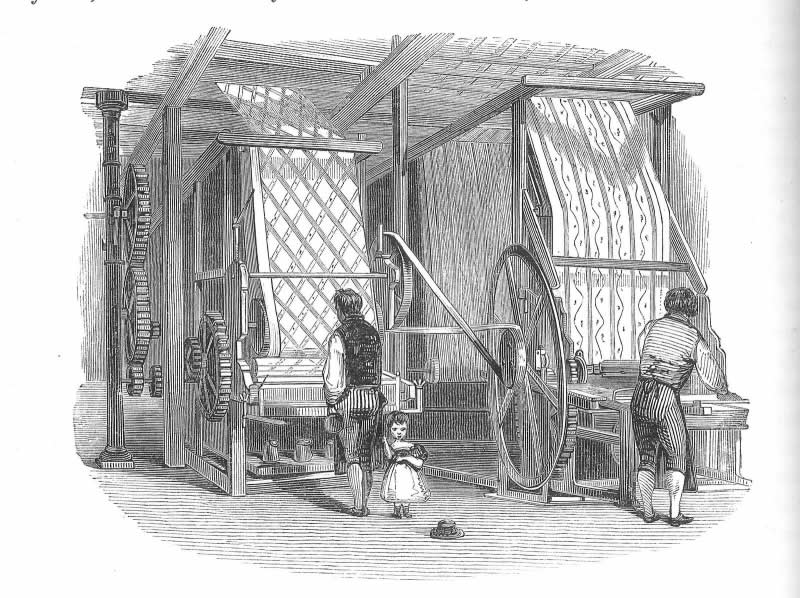

Pictorial History of the County of Lancashire, 1844.

Pictorial History of the County of Lancashire, 1844.

In the mid 1750s, the Society of Arts advertised a premium of £50 for ‘dyeing cotton yarn of the same red colour as that which is dyed in Turkey’. Several attempts were made to gather information about the processes used in Turkey, but it is most likely that the technique was first cracked by two Frenchmen, Borelle and Papillon, who set up Turkey-red dyehouses in Manchester and Glasgow.

It was much used in the dyeing of calico in this country when the concept of printing cloth was first developed in Manchester.

WELD or DYER'S WEED

Weld was cultivated as a source of yellow dye. It was also called dyer's rocket, dyer's mignonette and dyer's broom

Is a native plant of Britain, and was principally grown for dyeing in Essex. It gives a bright lemon green colour.

It was not expensive to buy and was later replaced by quercitron bark, certainly in calico printing. Books of husbandry in the 17th century regularly mentioned it as a profitable crop and not difficult to grow.

SAFFRON

Saffron comes from the autumn flowering crocus. As well as being imported from Europe, it was also grown in England.

“… but the English, as being fresher, more genuine, and better cured, is always preferred. Saffron is used in medicine, and in the arts; but in this country the consumption seems to be diminishing. It is employed to colour butter and cheese, and also by painters and dyers.

- Thomson's Dispensatory, Loudon's Ency. of Agriculture

It was grown in this country for dyeing and medicinal purposes, mostly around Saffron Walden where it was such an important part of the local economy, that it is represented on the town’s Coat of Arms. It was also grown in Essex, East Anglia and Cambridgeshire. It was considered to provide effective protection against the Black Death and its cultivation expanded in this country around that time - 1348/50.

“Saffron the best of the universall world groweth in this realme, and forasmuch as it is a thing that requireth much labour in divers sorts, and setteth the people on worke so plentifully …….It is reported at Saffronwalden that a Pilgrim purposing to do good to his countrey, stole an head of Saffron, and hid the same in his Palmers staffe, which he had made hollow before of purpose, and so he brought this root into this realme, with venture of his life: for if he had bene taken, by the law of the countrey from whence it came, he had died for the fact. If the like love in this our age were in our people that now become great travellers, many knowledges, and many trades, and many herbes and plants might be brought into this realme that might doe the realme good."

-Richard Hakluyt

"Sir Thomas Smith, secretary of State to Edward V1 and afterwards to Elizabeth, was born at Walden in the county of Essex, distinguished by the name Saffron Walden, the lands of that parish and the parts adjacent being famous for the growth of that useful medicinal plant; whether first brought thither by this Knights Industry (being a great planter) I know not, for it was first brought into England, as we are told in the reign of King Edward 111”

There is much evidence of it remaining in the Pennine area - around sites in West Yorkshire, well documented by the Halifax Antiquarians, in the Rochdale area as first documented in the Coucher book of Whalley Abbey (who governed the Rochdale area) and other places such as Derby and Nottingham.

In the upper valley, the evidence can be seen alongside many of our mills and old houses which include Makin Place, Holdsworthy House, Winteredge – both houses which belonged to the Knights Templar and Dyehouses in Luddenden.

We have started to put together a map showing the places in relation to the housing and mills which would have been there in the late 15th century. We will continue to add to this.

LICHEN DYES, ORCHIL AND CUDBEAR

Lichens were an important source of dye in medieval England providing purple and red known as Orchil and Cudbear. They were first dissolved in urine which acted as a mordant – fixing the dye to the fabric.

Cudbear is a dye that can be obtained from the orchil lichen. It is so called as it was named by Dr Cuthbert Gordon of Scotland after his mother. He started producing it after patenting the colour in Scotland in 1758. The exact production methods were highly secret with a 10ft wall being erected around the the place.

It produces a purple dye.

Mr Cuthbert’s brother, Cuthbert Gordon, published in the Scots Magazine (1755) certificates from dyers in Leeds, Halifax, Edinburgh and Glasgow, "that they frequently continued its use and found it answer their purposes well for dyeing linen, cotton, silk, and woollen goods to their great satisfaction both as to the elegance of the colours produced and the indigo saved" and they think that "Mr Gordon ought to be encouraged by every lover of his country for such a curious and valuable improvement".

A workman from Leeds wrote to the Chemical News in 1874, noting that there was no real practical information on the manufacture of archil and cudbear and offering the following:

"Archil Liquor is made by placing 300 pounds of Zanzibar orchella-weed into a cistern, covering with about 120 gallons of ammonia at 8^, steeping it a day and a night, ranning off the liquor into covered pans, which are heated with steam pipes underneath, and are in size 6 yards by 4, and 1 foot deep. The lid is removed once a day for about five minutes and the liquor is stirred. In about six weeks it is ready for storing or dyeing with.

Cudbear. — The weed is worked up in the same manner primarily, but instead of mixing the contents of the pans with salt and acid, they are dried by means of steam-heat on an iron plate about 10 yards square, and the dried mass is ground to powder.

Blue Archil is made by macerating in the cold (at the ordinary temperature?) 100 pounds of weed in 300 pounds of ammonia, 6^ strong, and turning the mass over twice a week for about ten weeks. Ph. CentralhalL, May 7th, 1874.

Other dyes had to be imported, at great cost, from abroad. These dyes included:

Cochineal comes from the cochineal insect originally from South America. It was discovered by the Spanish explorers of South America and Spain possessed a very lucrative monopoly of this expensive dye. In 1587 approximately 65 tons were shipped to Spain, and from there northward throughout Europe

Italian dyers already had an established red dye industry based on Kermes, which was made from the dried bodies of the scale insect. Cochineal red, however, was much more intense and cheaper and so was the preferred dye still in England.

Kermes is an older source of crimson dye and comes from a Mediterranean insect which were found in southern Europe on the small evergreen kermes oak. The history of the Kermes dye dates back to the ancient Egyptians and Romans. The words crimson in English and carmoisine in French are derived from the word.

Indigo began to replace woad in the 17th C as it became more available and woad growing declined. Woad growing in France, where it is known as Pastel, continued especially in the area around Toulouse

It came from the indigo plants of India and held colours fast and this rich color was worn by the wealthy. Indigo dye was produced, like woad by a process of fermentation, filtering and finally drying into cakes or balls of dye.

Tyrian Purple was made in the Lebanon by crushing thousand of a sea creature called a Mediterranean Murex, a type of whelk. It took ten thousand Murex molluscs to make the dye for just one toga! It was worth more than its weight in gold and came to be associated with wealth and power. Production of Tyrian purple almost ceased with the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when Queen Elizabeth was twenty years old, and was replaced by other cheaper dyes like lichen purple and madder.

In the Mediterranean counties, the shells were crushed to extract the dye, but Mexican Indians blow and tickle the whelks to get them to spit out the dye directly on to the yarn. The dye turns purple once it has been applied to the fibres and exposed to light and oxidation with the air. In Ireland there is evidence that whelks were used to dye wool using soapwort as the mordant.

Sumptuary Laws

The word “sumptuary” comes from the Latin verb “sumptus”; meaning “to consume” or “to spend”. Its traditional meaning, however, refers to the regulation and control of such consumption or expenditure.

Sumptuary laws are laws introduced to regulate consumption — traditionally by restricting clothing, food, or luxury goods — and in the process, enforcing visual reminders of an “appropriate” social hierarchy. Although not always effective, sumptuary laws were passed in Ancient Greece and Rome, as well as early Chinese, feudal Japanese and medieval Islamic societies. In these societies, sumptuary laws, with regard to clothing, often enabled easy identification of social groups, class divisions, or racial and religious difference (a more recent use of sumptuary legislation was seen in Nazi Germany, with the introduction of coloured badges as identifying markers).

In Britain, sumptuary laws were first seen with regard to ecclesiastic regulations, which detailed exactly what various members of the clergy were entitled to wear, and at what times. This is still in force, evidenced by the fact that the church is now looking at what is appropriate clothing for women vicars - commonly known as vicars in knickers!

Sumptuary legislation was extended throughout England from the Middle Ages until the seventeenth century, building on the legislation brought in by Henry 8th (1533) and Mary (1554). Particularly prescriptive statutes were published in the 1570s by Elizabeth 1st, who took sumptuary laws to the extreme with her Statute of Apparel in 1574.

These laws dictated the types and colours of clothing and fabric which different members of society could wear—in part to ensure that social groups could be easily identified, but also to support the English textile industry; a protectionist measure to limit spending on foreign textiles.

These stated that:

“...the superfluity of unnecessary foreign wares thereto belonging now of late years is grown by sufferance to such an extremity that the manifest decay of the whole realm generally is like to follow (by bringing into the realm such superfluities of silks, cloths of gold, silver, and other most vain devices of so great cost for the quantity thereof as of necessity the moneys and treasure of the realm is and must be yearly conveyed out of the same to answer the said excess)."

Extremely detailed lists of types of clothing were then published for both men and women, noting exceptions pertaining to rank or position. They were revised and amended numerous times by Parliament; but they were, in general, enforced both poorly and irregularly. The statute in question threatens those who did not modify their dress within twelve days of the statute’s publication with “pain of her highness’s indignation, and punishment for their contempt, and such other pains as in the said several statutes be expressed”. However, there was no system of effective enforcement or punishment to accompany the statutes, and they seem to have been inconsistently applied, and rarely adhered to:

The previous Acts of Apparel had all been disregarded and Elizabeth’s efforts were not much more successful and the people of England refused to observe the rules.

It is interesting to note that in contemporary society, clothing was often specifically singled out in wills and bequests, and could be extremely valuable. For example, in 1586, George Hargreave of Warley bequeathed “much apparel, including blue and russet coats, doublets, jerkins, one ‘trussing doublet’...”. likewise in 1568, James Newell of Heptonstall bequeathed to one relative “a velvet coat, a sackcloth doublet, and a pair of brown hose”.

John Mychell, also from Heptonstall, dictated in his will of 1555 that, “...also I gyve to Margarete, my dowghter, my best hatte, and to John Mechell, my sonne ... all my raymente excepte my blewe jacket”. This will doesn’t actually specify who should receive the “blewe jacket” in question, but as particular items of clothing were thought of, or sought after, so highly, one can conclude that the beneficiaries of such gifts would be unwilling to put a velvet coat, for example, away unworn due to a royal proclamation made so very far away from West Yorkshire.

It is notable that sumptuary laws introduced by Elizabeth’s representatives in Ireland at this time banned the wearing of traditional Irish garb, requesting that the native people dress in an English style. This crude method of controlling the population, one can imagine, was enforced with rather more vigour than its English counterpart.

Details of appropriate dress were particularly strict for those attending the Inns of Court, as detailed by Peter Goodrich:

“Other legislation ranged over the wearing of hats and gowns, the length of hair, the prohibition of beards, the color and types of cloth appropriate to different ranks of barrister, and the spirit and demeanor of members of the profession. Every detail of diet for every meal was exhaustively itemized. Who could eat what birds and what meat, and with what sauces, and with how much ale and wine was treated at length. All games and levity were forbidden, melancholic colors of dress were encouraged and at times required, and the last detail of decorum, from worship to personal habits and company frequented, were subject to scrutiny and judgment."

It was also seen to be important to regulate quantities of materials used — as shown in the 1562 Articles for the execution of the Statutes of Apparel:

"And for the reformation of the use of the monstrous and outrageous greatness of hose, crept alate into the realm to the great slander thereof, and the undoing of a number using the same, being driven for the maintenance thereof to seek unlawful ways as by their own confession have brought them to destruction: it is ordained as abovesaid that no tailor, hosier, or other person, whosoever he shall be, after the day of the publication hereof, shall put any more cloth in any one pair of hose for the outside than one yard and a half, or at the most one yard and three-quarters of a yard of kersey or of any kind of cloth, leather, or any other kind of stuff above the quantity; and in the same hose to be put only one kind of lining besides linen cloth next to the leg if any shall be so disposed; the said lining not to lie loose or bolstered, but to lie just unto their legs, as in some ancient time was accustomed; sarcanet, muckender, or any other like thing used to be worn, and to be plucked out for the furniture of the hose, not to be taken in the name of the said lining. Neither any man under the degree of a baron to wear within his hose any velvet, satin, or other stuff above the estimation or sarcanet or taffeta.”

This, too, was most likely intended to ensure that English textile production could meet the country’s needs, and maintain the security of supply without an overreliance on foreign imports. The pernicious influence of foreign fabrics and fashions was also viewed by some commentators with great suspicion:

“In A Quip, Greene attacks Italianated courtiers who, adopting ever finer fashions, lose themselves in pride and forget their duty to the poorer members of society. Greene’s Italianated courtier, Velvetbreeches, had been brought into England by his “companion Nufanglenesse.” Velvetbreeches had caused vast misery in English society, raising rents in an effort to finance his expensive lifestyle. Costly velvets, vainglory, and pride reigned at the expense of dignity, charity, and the honest country life.”

This nationalistic function of sumptuary laws was implemented in a slightly more subtle fashion in later centuries, through tariffs and a greater control of imported goods:

“From the mid-seventeenth century, efforts to promote the nation’s economy focused increasingly on the use of tariffs and other controls on trade to promote exports and to restrict imports. By the second quarter of the eighteenth century a situation had been arrived at where most foreign manufactures were subject to heavy import tariffs, so high in the case of France that a legal import trade was virtually impossible. Moreover, the import of certain classes of goods, Indian cottons and French alamode silks for example, was entirely prohibited.”

By proscribing such detailed nuances of costume, the sumptuary laws made transgressions of rank and class intimately linked to visual display. Some commentators have implied that the adoption of different modes of dress was thus, paradoxically, conducive to greater social mobility – or the appearance of mobility, at any rate.

“...[I]n medieval and early modern Europe, clothes signified social rank and habits of behaviour. People of every class and status participated in ceremonies of investiture: they put on habits as they put on “habits,” committing themselves to specific customs as they put on recognizable sets of apparel. To become rulers, master craftsmen, servants, wives or nuns, to be inducted into kingship, guild membership, an employer’s household, a marriage or a convent, meant putting on the livery and the expectations of that social group. Consequently, people of all classes read one another’s clothes as markers of their social identity. In an age of illiteracy, clothing was a widely legible sign of occupation, marital status, membership in particular groups, and wealth. And because it was complicated to put on and made of long-lasting fabrics (linen, wool, silk), it shaped the subjectivity of its wearers as well as its observers.”

Such clearly defined boundaries in terms of dress meant that methods of “transgression” were easily signposted; sometimes to comic effect – the codes of costume were so well-signalled by the Acts of Apparel that it was easy to recognise when someone was dressing “inappropriately”:

“... [I]n A Quip for an Upstart Courtier Robert Greene derided ‘every lowt’ who aspired to a higher social position. Now, Greene complained, no farmer was content that his son should hold the plow, and servile drudges rustled in their silks; these ‘dunghill drudges waxe so proud, that they wil presume to wear on their feet, what kings have worne on their heades."

Social critics were not simply concerned with the lower orders of society; many believed the higher orders were also at fault.

However, in extracts such as the following by William Harrison, we can see that restrictions on dress were not, perhaps, followed to the letter:

“But herein [Englishmen] rather disgrace than adorn their persons, as by their niceness in apparel, for which I say most nations do not unjustly deride us, as also for that we do seem to imitate all nations round about us, wherein we be like to the polypus or chameleon; and thereunto bestow most cost upon our arses, and much more than upon all the rest of our bodies, as women do likewise upon their heads and shoulders ... What should I say of [men’s] doublets with pendant codpieces on the breast full of jags and cuts, and sleeves of sundry colours? Their galligascons to bear out their bums and make their attire to fit plum round (as they term it) about them. Their fardingals, and diversely coloured nether stocks of silk, jerdsey, and such like, whereby their bodies are rather deformed than commended?”

Annex 1: Enforcing Statutes of Apparel

[Greenwich, 15 June 1574, 16 Elizabeth I] http://elizabethan.org/sumptuary/who-wears-what.html#note-budge

The excess of apparel and the superfluity of unnecessary foreign wares thereto belonging now of late years is grown by sufferance to such an extremity that the manifest decay of the whole realm generally is like to follow (by bringing into the realm such superfluities of silks, cloths of gold, silver, and other most vain devices of so great cost for the quantity thereof as of necessity the moneys and treasure of the realm is and must be yearly conveyed out of the same to answer the said excess) but also particularly the wasting and undoing of a great number of young gentlemen, otherwise serviceable, and others seeking by show of apparel to be esteemed as gentlemen, who, allured by the vain show of those things, do not only consume themselves, their goods, and lands which their parents left unto them, but also run into such debts and shifts as they cannot live out of danger of laws without attempting unlawful acts, whereby they are not any ways serviceable to their country as otherwise they might be:

Which great abuses, tending both to so manifest a decay of the wealth of the realm and to the ruin of a multitude of serviceable young men and gentlemen and of many good families, the Queen's majesty hath of her own princely wisdom so considered as she hath of late with great charged to her council commanded the same to be presently and speedily remedied both in her own court and in all other places of her realm, according to the sundry good laws heretofore provided.

For reformation whereof, although her highness might take great advantage and profit by execution of the said laws and statutes, yet of her princely clemency her majesty is content at this time to give warning to her loving subjects to reform themselves, and not to extend forthwith the rigor of her laws for the offences heretofore past, so as they shall now reform themselves according to such orders as at this present, jointly with this proclamation, are set forth, whereby the statute of the 24th year of her majesty's most noble father King Henry VIII and the statute made in the second year of her late dear sister Queen Mary are in some part moderated according to this time.

Wherefore her majesty willeth and straightly commandeth all manner of persons in all places within 12 days after the publication of this present proclamation to reform their apparel according to the tenor of certain articles and clauses taken out of the said statutes and with some moderations annexed to this proclamation, upon pain of her highness's indignation, and punishment for their contempts, and such other pains as in the said several statutes be expressed.

For the execution of which orders her majesty first giveth special charge to all such as do bear office within her most honorable house to look unto it, each person in his degree and office, that the said articles and orders be duly observed, and the contrary reformed in her majesty's court by all them who are under their office, thereby to give example to the rest of the realm; and further generally to all noblemen, of what estate or degree soever they be, and all and every person of her privy council, to all archbishops and bishops, and to the rest of the clergy according to their degrees, that they do see the same speedily and duly executed in their private households and families; and to all mayors and other head officers of cities, towns, and corporations, to the chancellors of the universities, to governors of colleges, to the ancients and benchers in every the Inns of Court and Chancery, and generally to all that hath any superiority or government over and upon any multitude, and each man in his own household for their children and servants, that they likewise do cause the said orders to be kept by all lawful means that they can.

And to the intent the same might be better kept generally throughout all the realm, her majesty giveth also special charge to all justices of the peace to inquire of the defaults and breaking of those orders in their quarter sessions, and to see them redressed in all open assemblies by all wise, godly, and lawful means; and also to all Justices of Assizes in their circuits to cause inquiry and due presentment to be made at their next assizes how these orders be kept; and so orderly, twice a year at every assize after each other circuits done, to certify in writing to her highness's Privy Council under their hands, with as convenient speed as they may, what hath been found and done as well by the justices of the peace in their quarter sessions, of whom they shall take their certificate for each quarter session, as also at the assizes, for the observing of the said orders and reformation of the abuses.

A brief content of certain clauses of the statute of King Henry VIII and Queen Mary, with some moderation thereof, to be observed according to her majesty's proclamation above mentioned.

None shall wear in his apparel:

Any silk of the color of purple, cloth of gold tissued, nor fur of sables, but only the King, Queen, King's mother, children, brethren, and sisters, uncles and aunts; and except dukes, marquises, and earls, who may wear the same in doublets, jerkins, linings of cloaks, gowns, and hose; and those of the Garter, purple in mantles only.

Cloth of gold, silver, tinseled satin, silk, or cloth mixed or embroidered with any gold or silver: except all degrees above viscounts, and viscounts, barons, and other persons of like degree, in doublets, jerkins, linings of cloaks, gowns, and hose.

Woolen cloth made out of the realm, but in caps only; velvet, crimson, or scarlet; furs, black genets, lucernes; embroidery or tailor's work having gold or silver or pearl therein: except dukes, marquises, earls, and their children, viscounts, barons, and knights being companions of the Garter, or any person being of the Privy Council.

Velvet in gowns, coats, or other uttermost garments; fur of leopards; embroidery with any silk: except men of the degrees above mentioned, barons' sons, knights and gentlemen in ordinary office attendant upon her majesty's person, and such as have been employed in embassages to foreign princes.

Caps, hats, hatbands, capbands, garters, or boothose trimmed with gold or silver or pearl; silk netherstocks; enameled chains, buttons, aglets: except men of the degrees above mentioned, the gentlemen attending upon the Queen's person in her highness's Privy chamber or in the office of cupbearer, carver, sewer [server], esquire for the body, gentlemen ushers, or esquires of the stable.

Satin, damask, silk, camlet, or taffeta in gown, coat, hose, or uppermost garments; fur whereof the kind groweth not in the Queen's dominions, except foins, grey genets, and budge: except the degrees and persons above mentioned, and men that may dispend £100 by the year, and so valued in the subsidy book.

Hat, bonnet, girdle, scabbards of swords, daggers, etc.; shoes and pantofles of velvet: except the degrees and persons above names and the son and heir apparent of a knight.

Silk other than satin, damask, taffeta, camlet, in doublets; and sarcanet, camlet, or taffeta in facing of gowns and cloaks, and in coats, jackets, jerkins, coifs, purses being not of the color scarlet, crimson, or blue; fur of foins, grey genets, or other as the like groweth not in the Queen's dominions: except men of the degrees and persons above mentioned, son of a knight, or son and heir apparent of a man of 300 marks land by the year, so valued in the subsidy books, and men that may dispend £40 by the year, so valued ut supra.

None shall wear spurs, swords, rapiers, daggers, skeans, woodknives, or hangers, buckles or girdles, gilt, silvered or damasked: except knights and barons' sons, and others of higher degree or place, and gentlemen in ordinary office attendant upon the Queen's majesty's person; which gentlemen so attendant may wear all the premises saving gilt, silvered, or damasked spurs.

None shall wear in their trappings or harness of their horse any studs, buckles, or other garniture gilt, silvered, or damasked; nor stirrups gilt, silvered, or damasked; nor any velvet in saddles or horse trappers: except the persons next before mentioned and others of higher degree, and gentlemen in ordinary, ut supra.

Note that the Lord Chancellor, Treasurer, President of the council, Privy Seal, may wear any velvet, satin, or other silks except purple, and furs black except black genets.

These may wear as they have heretofore used, viz. any of the King's council, justices of either bench, Barons of the Exchequer, Master of the Rolls, sergeants at law, Masters of the Chancery, of the Queen's council, apprentices of law, physicians of the King, queen, and Prince, mayors and other head officers of any towns corporate, Barons of the Five Ports, except velvet, damask, [or] satin of the color crimson, violet, purple, blue.

Note that her majesty's meaning is not, by this order, to forbid in any person the wearing of silk buttons, the facing of coats, cloaks, hats and caps, for comeliness only, with taffeta, velvet, or other silk, as is commonly used.

Note also that the meaning of this order is not to prohibit a servant from wearing any cognizance of his master, or henchmen, heralds, pursuivants at arms; runners at jousts, tourneys, or such martial feats, and such as wear apparel given them by the Queen, and such as shall have license from the Queen for the same.

Women's apparel

None shall wear:

Any cloth of gold, tissue, nor fur of sables: except duchesses, marquises, and countesses in their gowns, kirtles, partlets, and sleeves; cloth of gold, silver, tinseled satin, silk, or cloth mixed or embroidered with gold or silver or pearl, saving silk mixed with gold or silver in linings of cowls, partlets, and sleeves: except all degrees above viscountesses, and viscountesses, baronesses, and other personages of like degrees in their kirtles and sleeves.

Velvet (crimson, carnation); furs (black genets, lucerns); embroidery or passment lace of gold or silver: except all degrees above mentioned, the wives of knights of the Garter and of the Privy Council, the ladies and gentlewomen of the privy chamber and bedchamber, and maids of honor.

None shall wear any velvet in gowns, furs of leopards, embroidery of silk: except the degrees and persons above mentioned, the wives of barons' sons, or of knights.

Cowls, sleeves, partlets, and linings, trimmed with spangles or pearls of gold, silver, or pearl; cowls of gold or silver, or of silk mixed with gold or silver: except the degrees and persons above mentioned; and trimmed with pearl, none under the degree of baroness or like degrees.

Enameled chains, buttons, aglets, and borders: except the degrees before mentioned.

Satin, damask, or tufted taffeta in gowns, kirtles, or velvet in kirtles; fur whereof the kind groweth not within the Queen's dominions, except foins, grey genets, bodge, and wolf: except the degrees and persons above mentioned, or the wives of those that may dispend £100 by the year and so valued in the subsidy book.

Gowns of silk grosgrain, doubled sarcenet, camlet, or taffeta, or kirtles of satin or damask: except the degrees and persons above mentioned, and the wives of the sons and heirs of knights, and the daughters of knights, and of such as may dispend 300 marks by the year so valued ut supra, and the wives of those that may dispend £40 by the year.

Gentlewomen attendant upon duchesses, marquises, countesses may wear, in their liveries given them by their mistresses, as the wives of those that may dispend £100 by the year and are so valued ut supra.

None shall wear any velvet, tufted taffeta, satin, or any gold or silver in their petticoats: except wives of barons, knights of the order, or councilors' ladies, and gentlewomen of the privy chamber and bed chamber, and the maids of honor.

Damask, taffeta, or other silk in their petticoats: except knights' daughters and such as be matched with them in the former article, who shall not wear a guard of any silk upon their petticoats.

Velvet, tufted taffeta, satin, nor any gold or silver in any cloak or safeguard: except the wives of barons, knights of the order, or councilor's ladies and gentlewomen of the privy chamber and bedchamber, and maids of honor, and the degrees above them.

Damask, taffeta, or other silk in any cloak or safeguard: except knights' wives, and the degrees and persons above mentioned.

No persons under the degrees above specified shall wear any guard or welt of silk upon any petticoat, cloak, or safeguard.

“In the context of the ecclesiastical polity and a law that was explicitly both divine and human, the regulation of dress, ornament, and food was linked to a theological and moral concern with the proper signs of identity and community.” Peter Goodrich, “Review: Signs Taken for Wonders: Community, Identity, and ‘A History of Sumptuary Law’”; Reviewed work: “Governance of the Consuming Passions: A History of Sumptuary Law” by Alan Hunt (1998) 23(3) Law & Social Inquiry 707, 711

Statute issued at Greenwich, 15 June 1574, 16 Elizabeth I.

Liza Picard, Everyday Life in Elizabethan England (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003), p.135.

“Gleanings from Local Elizabethan Wills”, H.P. Kendall (Transactions of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, 1915) 113, 136

“Gleanings from Local Elizabethan Wills”, H.P. Kendall (Transactions of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, 1915) 113, 137

“Halifax Wills Vol. II 1545–1559”, ed. E.W. Crossley, privately printed for the author (1952), p.110.

“The only textile fibres then were silk, linen, cotton, wool and hemp. Silk could be spun into thread of varying thickness, and woven into fabric of different weights and appearance, from the finest gauze (‘cyprus’, ‘sarcenet’, which was much used for linings, and ‘tiffany’, used for puffs) to taffeta, which was not quite so fine, velvet, plush (a deeper pile than velvet) and satin, particularly the satin woven in Bruges (‘satin of Bridges’). ‘Tissue’ was woven from silk thread twisted round a gold or silver core. Linen could span the gamut from the finest gossamer-weight Holland and lawn for ruffs, to heavyweight dowlas and lockram for working men’s shirts. A blend of linen and wool made linsey-woolsey and fustian, much used for hard-wearing breeches.” in L. Picard, Everyday Life in Elizabethan England (2003), p.137.

P. Goodrich, “Review: Signs Taken for Wonders (1998) 23(3) Law & Social Inquiry 707, 721.

Also known as “sarcenet”; a fine, thin, woven silk fabric made both plain and twilled, in various colours.

A handkerchief or bib.

Robert Greene, A Quip for an Upstart Courtier (1592), in The Life and Complete Works in Prose and Verse of Robert Greene M.A., ed. A.B. Grosart (London, 1881–1886).

Modern England” (1995) 26(4) The Sixteenth Century Journal 881, 892.

John Styles, “Product Innovation in Early Modern London” (2000) 168 Past and Present 124, 130.

Ann Rosalind Jones, “Habits, Holdings, Heterologies: Populations in Print in a 1562 Costume Book” (2006) 110 Meaning and Its Objects: Material Culture in Medieval and Renaissance France 92, 93–4.

Robert Greene, A Quip for an Upstart Courtier (1592), in The Life and Complete Works in Prose and Verse of Robert Greene M.A., ed. A.B. Grosart (London, 1881–1886).

S.Warneke, “A Taste for Newfangledness” (1995) 26(4) The Sixteenth Century Journal 881, 891.

William Harrison, “Description of Elizabethan England” (1577), in Holinshed’s Chronicles [available at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1577harrison-england.html#Chapter%20VII], Book III, Ch.2.